Equity and the Vaccine Rollout

“We don’t want equity and speed at odds with one another,” said California’s Health Secretary Mark Ghaly at a recent news conference. As the COVID-19 vaccine rollout approaches its third month, more information is now available to assess state efforts at balancing these tasks. In the past week, a number of pieces have been published that focused on whether state distribution processes were resulting in people being left out or behind because of their race, income, geographic location, mobility, English language skills, technology access or savvy, and/or other factors. As we know, during the pandemic, black, Hispanic, and Native American populations have suffered disproportionate levels of COVID-19-related deaths, hospitalizations, severe cases, and overall rates compared to non-Hispanic white populations.

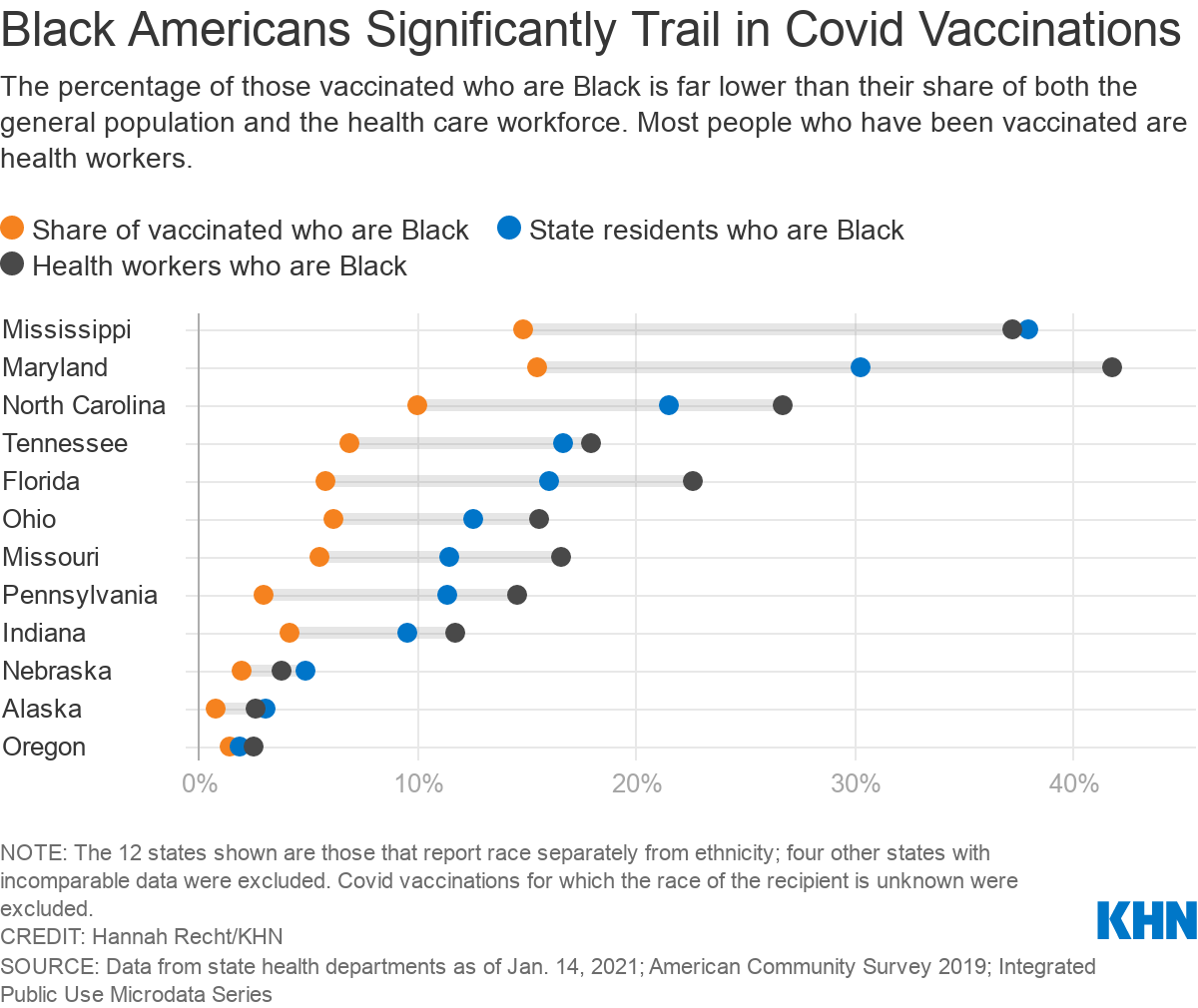

Kaiser Health News published a report based upon the rollout data available from 23 states (including Indiana). The authors found that blacks in those states not only were getting vaccinated at lower rates than whites, but in most states the share of blacks who had been vaccinated was lower than the share they make up in those states’ general population and in the states’ population of health care workers. See the chart below:

It appears clear that the Biden Administration will be holding states more accountable than the prior administration concerning addressing issues of equity in the vaccine rollout and COVID-19 response overall. Beginning this week, this will include publishing data similar to the above on a weekly basis.

What steps are states taking to address these disparities?

A. Risk Maps & Disadvantage Indices

A recent study in Nature Medicine suggests that policymakers use risk-based vaccination prioritization strategies, using tools such as COVID-19 mortality risk calculators and COVID-19 risk maps to prioritize outreach resources and efforts toward neighborhoods that likely will see relatively higher rates of COVID-19 deaths. (Thanks to Dr. Elaine Hernandez for sharing this reference!)

These maps, along with so-called “disadvantage indices” that highlight health and social disparities, like the Social Vulnerability Index, the Pandemic Vulnerability Index and the Area Deprivation Index can be “the country’s compass for equitable distribution of Covid-19 vaccines” says Harald Schmidt (also see his lead-authored article analyzing state distribution plans).

Specifically, Disadvantage Indices can help states:

- “[Plan] where to place dispensing sites so locations are easy to reach, especially for disadvantaged populations who may have less flexible working hours, informal caring obligations that make it difficult to spend several hours on a vaccine appointment, or transportation challenges. New Jersey already indicates it is doing this. This approach will also help plan locations for nontraditional sites for vaccinating Americans such as school gyms, sports stadiums, community centers, and mobile clinics that were announced under the Biden administration’s national strategy.”

- “[P]lan outreach and communication strategies, something that Arizona, Vermont, and Washington are doing.”

- “[E]nsure that more vulnerable groups are offered larger shares of vaccines each time a state or city-level jurisdiction receives a new batch. Doing so reduces scarcity for these groups and means they can receive vaccines more quickly. In adapting the National Academies proposal for equitable allocation, planners in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Tennessee already adjust the number of vaccines shipped to allocation sites so more-vulnerable populations are offered more than they would have received based on numbers alone. This approach can also counteract the tendency of better-off and well-connected groups to work the system to their advantage.”

- “[M]onitor equitable allocation and course-correct, where needed”.

B. Equity Pay-for-performance

California, in addition to changing their prioritization approach and turning over to Blue Cross responsibility for overseeing their vaccine distribution process, has indicated it will implement a pay-for-performance plan, paying bonuses to vaccine providers who direct a higher share of their vaccination efforts toward poor and vulnerable communities. In states where tactical decisions concerning the distribution process have been delegated down to the local level, this results-oriented approach may be a way to improve reporting and instill accountability for equity without micromanaging how sites run.

Since black and Hispanic populations have been disproportionately adversely affected by the pandemic, couldn’t a state use race alone as a factor in distribution decisions? Probably not. Last week, Oregon’s vaccination distribution advisory committee considered explicitly considering race as a factor in how vaccines would be distributed; however, they backed away from making such recommendations, as such an approach would likely be unconstitutional.

Finally, I’m pleased to share two recorded events I participated in this past week in which I discuss the vaccine rollout:

- How Is Indiana’s COVID-19 Vaccine Rollout Going? – A Side Effects Public Media/Indiana Public Broadcasting Facebook Live event featuring Dr. Virginia Caine of the Marion County Health Department, me, and public radio’s Lauren Chapman.

- Emergency Use Authorizations: Vaccines, therapies, diagnostics & policy – A BioCrossroads Frameworx event that included presentations from an array of life sciences and policy experts

Federal Mask Mandate

The Centers for Disease Control has issued an order requiring most people over age 2 to wear a mask “while boarding, disembarking, and traveling on any conveyance into or within the United States,” as well as at any transportation hub (such as airports and train, bus, subway, and rail stations) within the United States. The order’s definition of a mask is either a homemade or manufactured covering that “should be a solid piece of material without slits, exhalation valves, or punctures,” and that completely covers the nose and mouth of the wearer when properly worn. A face shield does not qualify as a mask. They set this mandate up as part of their process of trying to ensure “controlled free pratique,” or conditions that permit transportation to enter and exit locations while remaining free from contagious disease. The orders were issued under 42 U.S.C. 264 (Section 361 of the Public Health Service Act), and the Interstate Quarantine provisions found in 42 C.F.R. sections 70.2, 71.31(b), and 71.32(b).

These rules are a strong step by the federal government to start establishing the importance of mask wearing in crowded public settings that are essential to keeping essential workers protected from COVID-19 and to keep our economy running. While the breadth of these rules will likely be challenged, especially when it comes to imposing requirements on purely in-state travel, the federal government argues the following:

Traveling on multi-person conveyances increases a person’s risk of getting and spreading COVID-19 by bringing persons in close contact with others, often for prolonged periods, and exposing them to frequently touched surfaces. Air travel often requires spending time in security lines and crowded airport terminals. Social distancing may be difficult if not impossible on flights. People may not be able to distance themselves by the recommended 6 feet from individuals seated nearby or those standing in or passing through the aircraft’s aisles. Travel by bus, train, vessel, and other conveyances used for international, interstate, or intrastate transportation pose similar challenges.

Intrastate transmission of the virus has led to – and continues to lead to – interstate and international spread of the virus, particularly on public conveyances and in travel hubs, where passengers who may themselves be traveling only within their state or territory commonly interact with others traveling between states or territories or internationally.

In other news concerning mask mandates, a lawsuit that had been brought to challenge a mask mandate by the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma recently was dismissed with prejudice.

Eviction Moratorium Extended

Earlier this past week, the CDC also extended the national eviction moratorium through March 31, 2021. While this may prevent many Americans from being unhoused as a result of economic hardships they may be suffering due to the COVID-19 pandemic, housing experts criticize that the eviction moratorium fails to address a number of structural problems that will continue to allow some renters to be evicted, and does not address the heavy financial impact of continued deferral of rental payments on landlords.

Closing Thought

As we continue to work to develop and implement evidence-based policies, programs, and practices to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, I am regularly reminded of this quotation:

“To study COVID‑19 is not only to study the disease itself as a biological entity,” says Alondra Nelson, the president of the Social Science Research Council. “What looks like a single problem is actually all things, all at once. So what we’re actually studying is literally everything in society, at every scale, from supply chains to individual relationships.”

Thanks to the leadership of the Monon Collaborative for recognizing this as a concern and a need, and for bringing together this interdisciplinary group of experts to aid our collective sense-making here in Indiana during this time.